Inside Entrepreneur First: a survival guide for the world’s most exclusive talent accelerator

Billion dollar aspirations, break ups, and more

Almost 9 months ago to this day, I found myself sat in a spartan, brick wall office in a non-descript corner of Bermondsey, South East London. Spread around me were 70 other hopefuls, joining Entrepreneur First – the world’s most exclusive ‘talent accelerator’ - because they believed they had a billion dollar company somewhere inside them. Self styled as the best place in the world to meet a cofounder, EF helps a bunch of hyper driven weirdos to find their match and build a venture backable ($1bn+) startup in the shortest possible time.

These herculean ambitions sound lofty but aren’t exactly unfounded. Already, people that met on my cohort have gone on to raise $ms from top investors like Index Ventures. On average, there has been at least one $100m+ company in each EF cohort, with past big hitters including computer vision unicorn Tractable, Credit Kudos (acquired by Apple for $100m+), Magic Pony (acquired by Twitter for $150m+) and Omnipresent, valued at $700m+ barely 2 years after founding. If you want to build a serious company, EF is one of the best places in the world for you to do it.

The idea behind this essay is to lift the lid on what actually happens during EF. I want to share some tips and tricks for surviving what is, without a doubt, one of the most intense career experiences you can put yourself through. I tried to approach EF in a structured way and hope some of the heuristics I used (and the mistakes I made) can help future founders navigate some of the tricky decisions they’ll face. Let’s get to it.

What on earth is a talent accelerator?

Let’s say that you want to found a company, but you don’t know the right cofounder. What do you do?

For the past few decades you generally didn’t have a choice. You either shack up with a friend/colleague or decide to go it alone. But what if Sergey Brin and Larry Page didn’t meet at Stanford? Would the world have lost out on Google and over a trillion dollars in economic value?

EF’s thesis is exactly this: the world is missing out on some of its best entrepreneurs. If you can make the process of finding a cofounder seamless – and in doing so derisk entrepreneurship as a career choice - more world changing companies will be built. Magic Pony, EF’s earliest success story, is an almost poetic validation of this idea. Cofounders Rob Bishop and Zehan Wang both studied at Imperial College London in the same year, yet didn’t meet each other until they joined EF. A little over 18 months after founding, they sold their machine learning startup Magic Pony to Twitter for a cool $150m.

So how does this work in practice? EF takes 70-80 selectively chosen future founders, roughly half technical (CTOs) and half commercial (CEOs), in biyearly cohorts and helps them to rapidly iterate through different cofounder pairings. The first half of EF, known as ‘Form’, gives you 8 weeks to find your perfect cofounder match. If you find them, you get to pitch at EF’s Investment Committee (IC) 4 weeks later for £80k in pre-seed funding. If you don’t - as happens to circa 50% of the cohort - you get kicked off EF.

The best analogy here is dating. EF is something like the illegitimate love child of Love Island and the Imperial College London computer science department, with a dash of the Hunger Games thrown in. You’ll need to court your cofounder match, while developing your startup problem thesis and avoiding all of the trap doors that can lead EF (or burn out) to take you out of the game. Sound fun? Read on.

How EF actually works (not how they say it works)

There is an open secret at EF: the programme starts 4-5 weeks before the ‘official’ start date.

Roughly five weeks before the official EF start date, you’re invited to a cohort Slack group and an Airtable with profiles of each cohort member. To be crystal clear: the moment the Airtable goes live is when EF actually starts. You should be prepared to start grafting the moment you get the invite. Do not use this time to hit the tables in Vegas or head off on a honeymoon.

Put together, the real timeline looks something like this:

Week -5: the cohort Slack and Airtable (a searchable database of every cohort member) go live

This is when EF actually starts.

Week -3: Kick Off Weekend

This is the first official EF event, where you get to meet all of the other cohort members.

Week 1 - EF Form begins

This is when EF officially starts and the countdown now begins. You have 8 weeks to be in a stable cofounder team or you get the boot.

Week 8

If you’re not in a stable cofounder team by this point, you have to leave.

C. 50% of the EF cohort get marching orders at this point – you’re down to about 35 people

Week 10 - SCI

A test run at IC

Week 12 - IC

The pitch where the EF investment committee decide to fund you with a small pre-seed (£80k) or not

C. 30-35% of the remaining teams get funded – by this point you’re down to about 8-10 teams

Launch begins

During Launch, the EF team huddles around your nascent company to help you raise a seed (£1-5m) from VCs

The Airtable includes a bio of every cohort members and their answers to questions like ‘what is the most impressive thing you've built?', ‘what skills are you seeking in a cofounder?’, and ‘what sectors do you want to work on?’. This will be your de facto CRM for the next few weeks. You should duplicate this Airtable into a private version and use this for note taking and list building.

The big promise of EF is human talent and boy do they deliver. I’ve never felt such intense impostor syndrome as when I scrolled through the cohort Airtable for the first time. I grew into my edge over time, but my first initial thought was something along the lines of “how the fuck am I going to compete with these people?”. It’s easy at first glance to undervalue your own worth and over index on the paper achievements of others. When you meet them in the flesh and realise that, like you, they are flawed human beings with strange quirks, reality sets back in.

Here are a few snapshot examples of the people on my cohort:

A Cambridge educated doctor with a triple first and a DeepMind funded MSc in computer science, graduating (unsurprisingly) with a high distinction

An Oxford Physics PhD who published research in Nature

An early Robinhood engineer who graduated from school at 14 and then took an Ivy League CS degree

A former PE investor who had almost every prestigious badge you could think of: Stanford, McKinsey, Morgan Stanley

A two time commercial founder who had raised $ms from tier 1 VCs straight out of university

A Oxford educated software engineer that quit their high flying finance job to build an algorithmic crypto trader, threw their life savings behind it, and never had a down day in 2.5 years (this is the guy I went on to cofound with)

From plank world record holders, ex IDF spec ops pilots, not one but three ultra marathon runners, even former X Factor finalists – not a single person on EF is ‘normal’ in the traditional sense of the word.

Finding a cofounder: EF meets Hinge

Great, so now you’re surrounded by the best and brightest. How do you secure one of them as your cofounder?

If you’re a rationalist nerd - and I’m assuming this is a large part of my audience - you’ve probably heard of the secretary problem of optimal stopping. In plainer English, this problem relates to situations where you can either stick with what you have or take your chances on something new. Classic examples are choosing when to commit to a romantic partner vs continuing dating, or deciding when to make an offer to an aspiring candidate vs interviewing more people.

Taking inspiration from this problem, the first maxim to live by in choosing an EF cofounder is not to match with your first love. You need to play the scene and evaluate cohort members until you have enough information to make actual comparisons between cofounders. It doesn’t matter how much chemistry you have with the first 5 people you speak to, you can’t make an informed decision until you have spoken to a bigger sample of the cohort.

Kick Off Weekend (KOWE) is a useful forcing function here, since this is when the cascade of cofounder pairings begins – the best cofounders on EF all go off the market in the 2 weeks immediately after KOWE.

The most optimal strategy based on this dynamic is to speed run EF before it starts. In the 2-3 weeks before kick off weekend, speak to everyone who you could cofound with. Not most of them, all of them. This is your chance to gather as much information as possible before your options begin to dwindle as people pair up. It doesn’t matter if you have a job at this point, you need to get it done in the evenings/weekends. This will give you the info you need to build a list of the 5 best matches so you can go onto KOWE - ahead of many of your peers who are meeting people for the first time - and court your future cofounder with confidence.

If you take 7-8 intro calls a day and a few over the weekend, it’s feasible to speed run this in a week. This is roughly what my days looked like:

Evaluating cofounders

It’s a truth universally acknowledged that all cofounders are not created equal. You don’t want to work with someone who will ditch you when the going gets tough so it’s important to think carefully about how you evaluate cofounders beyond their paper credentials, too.

There is no simple answer to this question - it’s more art than science - but there are a few heuristics that you can use:

Ask structured questions

Vet for motivation

Search for gold dust

Structured questions

You should make sure you ask structured questions to get high quality, standardised information, just as you would if trying to interview job candidates and make intelligent comparisons between them. If you go into each first meeting and YOLO your way through whatever random questions happen to be on your mind, it will be much harder to make fair comparisons.

That said, don’t run your conversations like an interview. It needs to feel like a natural back and forth or you’ve screwed it and will obliterate any chemistry before it’s had a chance to bloom. You can keep it simple by making sure that you ask everyone the same 3-4 core questions, e.g:

What’s your background? (context)

Why are you doing EF? (motivation)

What do you want to work on? (intent)

What are you great at? (differentiator)

Keep your questions open and don’t double-barrel them. Take notes on your answers and add it to whatever CRM you’re using (Notion, Airtable, etc). You will speak to so many people in the first few weeks of EF that you will forget entire conversations in a matter of minutes. Record everything and make notes on clear next steps.

Both of the cofounders I worked with on EF said that they liked this about how I approached speaking to them. They complained that some other founders vacillated and rambled – the more structured approach shows a sense of purpose.

If the first conversation goes well, close a follow up session to focus on ideation. You always want to be moving forwards with people that you rate.

Vet for motivation

You need to understand not just what someone wants to do, but why they want to do it. This will both help you to close them as a cofounder - if you know what they care about, the sale becomes easy - and figure out if they’re in this for the right reasons.

I’ve heard stories of EF teams that broke up just before pitching the Investment Committee because one cofounder decided to join Goldman Sachs, and another that packed it in because they didn’t want to lose their medical license. You don’t want to pour months worth of effort into a partner that is going to flake on you so do your homework first.

Startups weren’t as popular 10 years ago. To accrue social prestige at your elite college, you founded a charitable foundation, not a company. As startups enter the public zeitgeist and become cool, you’ll have to stay wary for entrepreneurial LARPers – the people who are in this for the prestigious cofounder stamp and endless podcast invites, that spend all of their time waxing lyrical about what they want to do, with a suspicious lack of doing.

Has someone got excellent, prestige credentials - all the top universities and consultancies - but no clear ‘why’? Run for the hills. They are not in this for the long haul and that matters when the the average startup takes 7-9 years to exit, and when much of which - as Elon Musk once said - feels like chewing glass and staring into the abyss.

As EF accrues more and more prestige, slowly approaching a gilded Y-Combinator like status in Europe, the bigger this issue of motivation becomes. EF does an admirable job of weeding most of these people out, but they can’t catch them all.

Gold dust

In Paper Belt on Fire, a recent book recounting the early days of the Thiel Fellowship, author and billionaire scout Michael Gibson lists some of the common traits that they found in successful applicants, from Dylan Field (Figma CEO/cofounder) to Vitalk Buterin (Ethereum founder):

Emotional resilience, sustaining motivation, tensive brilliance, egoless ambition, edge control, crawl-walk-run, hyperfluency, and friday night dyson sphere.

The important part here is Michael’s conclusion. Beyond all of these abstractly worded traits, even raw IQ, there is a fundamental, human core that all great founders share:

“This virtue isn’t so much about knowing the right way versus the wrong way, or the light versus the dark side of the force, but about two dark ends and a thin light wedge opening in the middle, which the very best shot through repeatedly to hit the market. It is all about character … the great founders are the ones who always find a way. This is their highest virtue”

Put simply, they are tricky bastards who get things done and refuse to die. This is what you need to look for, beyond paper credentials, and is where cofounder matching becomes most subjective. Let’s look at a few examples.

Maybe a potential cofounder has less overt signals of prestige, but has spent the last 4 years changing careers and working prodigiously in the evenings/weekends to learn how to code, land a software engineer role at a top company, and get into EF. This kind of trajectory is planned years in advance and is hard to execute – it’s a gold dust signal. If someone has made sacrifices in the past, this is the best possible indicator for how they will act in the future.

Another case in point: EF’s first $bn+ founder, Alex Dalyac of Tractable. He applied to EF and got rejected for lacking technical ability (he was an ex hedge fund trader). Alex then spent a year studying AI at Imperial (winning prizes along the way, despite no prior CS degree) and got into EF on his second try. He had to graft to get into EF and didn’t let the first rejection turn him away – that was a strong indicator to his potential cofounders that he would continue to refuse to take no for an answer in the future. Given how successful Tractable has been, I’m assuming he’s kept this up.

Or take my cofounder for example. He had a cushy job as a software engineer in a high frequency trading company. The money was rolling in and life was good. He quit his job to build an automated algo trader from his bedroom, funded with his life savings, and in 2.5 years never had a down day. Taking the hard route takes a certain kind of person – this could have blown up in his face.

More broadly there are a few other sub traits that you should search for:

Superhuman levels of grit and determination

What have they overcome in their lives? Have they achieved something brilliant when the odds were stacked against them? When have they dealt with adversity?

If someone has gone to an elite private school in the Swiss alps, matriculated to Bocconi for a finance degree, then landed in a cushy VC role straight out of university, they have the paper credentials – but what have they really overcome? Arguably they’ve just done what is expected of them their entire lives. You need to dive deeper.

Speed

When has this person done something inordinately quickly? Did they try to cram a 4 year PhD in 2 years or graduate from high school early?

Sam Altman, the former Y Combinator president, once quipped that when comparing great YC founders against average YC founders, the difference in speed was stark: even responding to important emails, great founders took minutes, average founders days.

The best teams on EF are almost always also the fastest. Make sure your cofounder can keep up, especially if they’re used to a less frenetic pace (big tech, consulting, academia etc)

This guy would be an excellent EF candidate, without the legal troubles

Decisiveness

Part of this is the ability to stare into the abyss, to confront uncomfortable decisions with a surprising degree of joy and without delay

The Firstround Review cofounder dating playbook has a useful question list for getting into these themes. If you really want to get ahead of the game, you can write out your answers in a Notion doc and use this as a prop for a conversation with potential cofounders.

Getting over breakups

One of the strangest EF experiences is breaking up your team. Unlike in real dating, this is encouraged and celebrated, since the opportunity cost of being in the wrong team is so incredibly high. It still takes an emotional toll though. When I broke up my first team after 3 weeks of intense work, it felt like killing a short relationship.

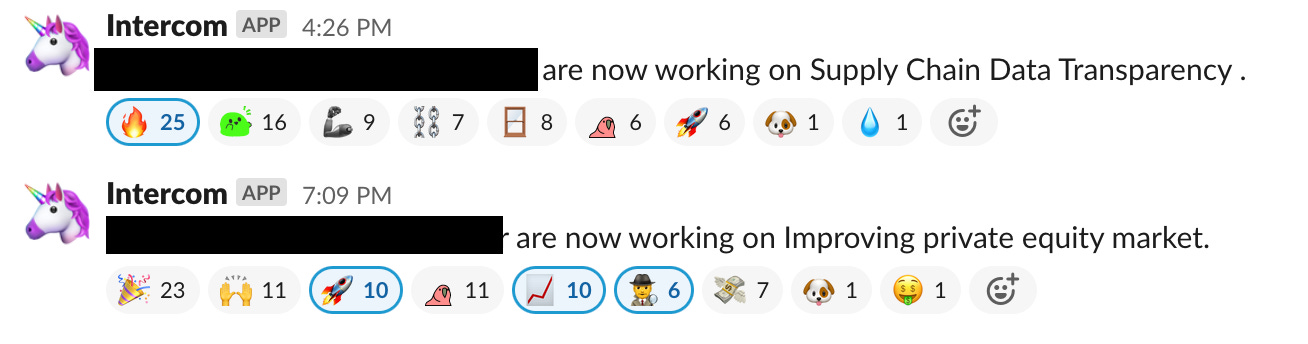

In a Slack channel called team-formations, every single new cofounder pairing and breakup is announced automatically in real time. You’ll often get a notification and think “Shit, (top cofounder) is free. Time to frantically search the office and grab them so we can go for a walk”. And you’re not the only person doing this: if that person is in demand, every solo founder on the cohort will be circling like a pack of hungry (but friendly) vultures. This is where the Love Island analogy reaches its peak – it adds to the pace of what is already a frenetic cofounder dating experience.

Ramping up the pressure even more is the EF programme team. The programme team act as pseudo marriage counsellors and matchmakers. If you’re single, they’ll suggest cofounder matches for you, and if you’re in a team, they’ll give you weekly counsel and frequently pressure you to break up your team.

It’s important to pause here to think about incentives. You are incentivised to get the best possible personal outcome. EF is incentivised to create the best possible teams. The power law that governs VC returns means that the best teams are the only ones they truly care about – the mid rankers won’t get anywhere near to being fund returners. Perhaps you are part of the best possible team, in which case EF and your incentives are aligned. But maybe you’re not.

So, when you go into a room with the EF team and they are telling you to break up your team, you need to take their advice with a grain of salt. They are optimising for great teams, not your individual outcome. They could see your cofounder as a top 10%er, and you as a mid ranker, and they want to break up the team not because you are doing badly per se, but to liberate your cofounder get a match with someone they rate more highly. Equally, they might rate you highly and think that your current cofounder is dragging you down, even if you have some traction.

During week 4 of our cohort this descended into a Game of Thrones esque red wedding scene when the EF team went on a behind the scenes murder spree. Pretty much every single team that had been paired for ≥ 1 week was put under intense pressure to kill their team. You’d often walk past a forlorn figure sat outside the EF campus with their head in one hand, and a cigarette in the other. Most buckled from the pressure - including me - which added liquidity to the solo founder market and reshuffled the deck. Some stuck it out and a few of them, as far as I know, got funded by EF.

The ultimate metric that should govern your decision here is traction. If you and your team mate are generating good traction and learning new things every day, you should feel free to ignore the EF team if they are telling you to break up. And make sure here you are comparing your traction to the best founders on the cohort – winning in a vacuum is meaningless. If you’re not moving faster than everyone else, you should listen to EF’s advice and pull the trigger.

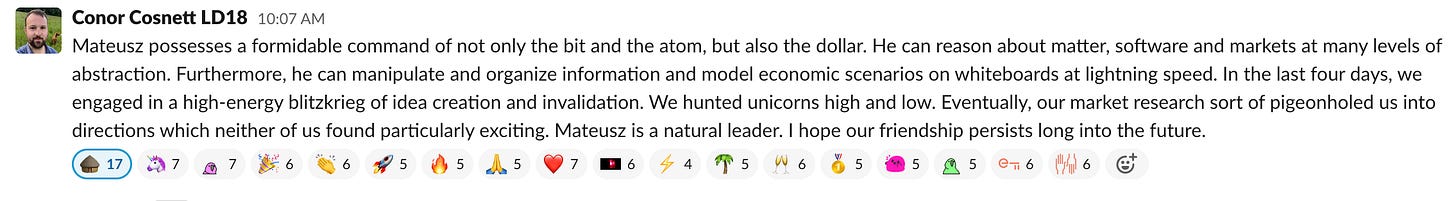

A more cheery part of team explosions is an EF tradition where you write a kind of cofounder eulogy to celebrate your break up. A whipsmart Irish engineer on our cohort called Conor turned this into an art form:

Here are a few tips on a process you can run after a break up:

If you were working together for a long time, take a day / half day off

If you’ve done EF right, you will have been sprinting until this point. Taking a short break gives you the space to do some thinking about what you want to work on next. This is the pretty much the only time I will encourage you to take a break.

Lots of people go into EF thinking “I will only work on X (e.g. climate)” and by the end of EF are working on something completely different. Use each break up to reorient what you want to work – do you want to stick to your guns and only do X or are you open to something new?

If you aren’t purposeful about this, you will get dragged into fashionable areas (e.g. Web3) that you don’t really care about, so be careful.

Make a list of all the problems / workaround solutions you’ve seen in your career

You will have (presumably) exhausted the first few problems that you wanted to work on.

Thinking about past workarounds can be a goldmine of ideas. You only build a workaround if you truly care about solving a problem, which derisks the problem space.

Companies like Incident.IO ($34m Series A) is a productised version of a Slackbot workaround that Monzo’s engineering team built. Cord ($17.5m Series A) is a productised version of an internal Facebook tool. There are more Incident.IOs and Cord’s out there waiting to be built.

Go out to all relevant solo founders and throw them problems from that list – see which ones get people excited

If you come to a shared belief, pair up with that person ASAP. Since you’ve done your homework on every possible cofounder before KOWE, at this point your mentality should be ‘easy in, easy out’.

You should already know them pretty well from your earlier intro call blitz, but it doesn’t hurt to reference them with former cofounders to see how they work and if they have any flaws.

I used this process and within a few days of my first breakup, had 3 offers from good cofounders to work with me.

The mistake that killed my company

A part of this story has been missing: what about my company?

I went into EF with an edge - a ‘right to win’ - in Talent, since I’d helped to build an early stage SaaS company from 0 customers to Series B tier size and $Ms in ARR + profitability. But at first, I didn’t want to build in talent. Frankly, I was bored of the space. It was full of old problems and a tricky user base. You want to be fascinated by your users, and I questioned if I could find that again in talent.

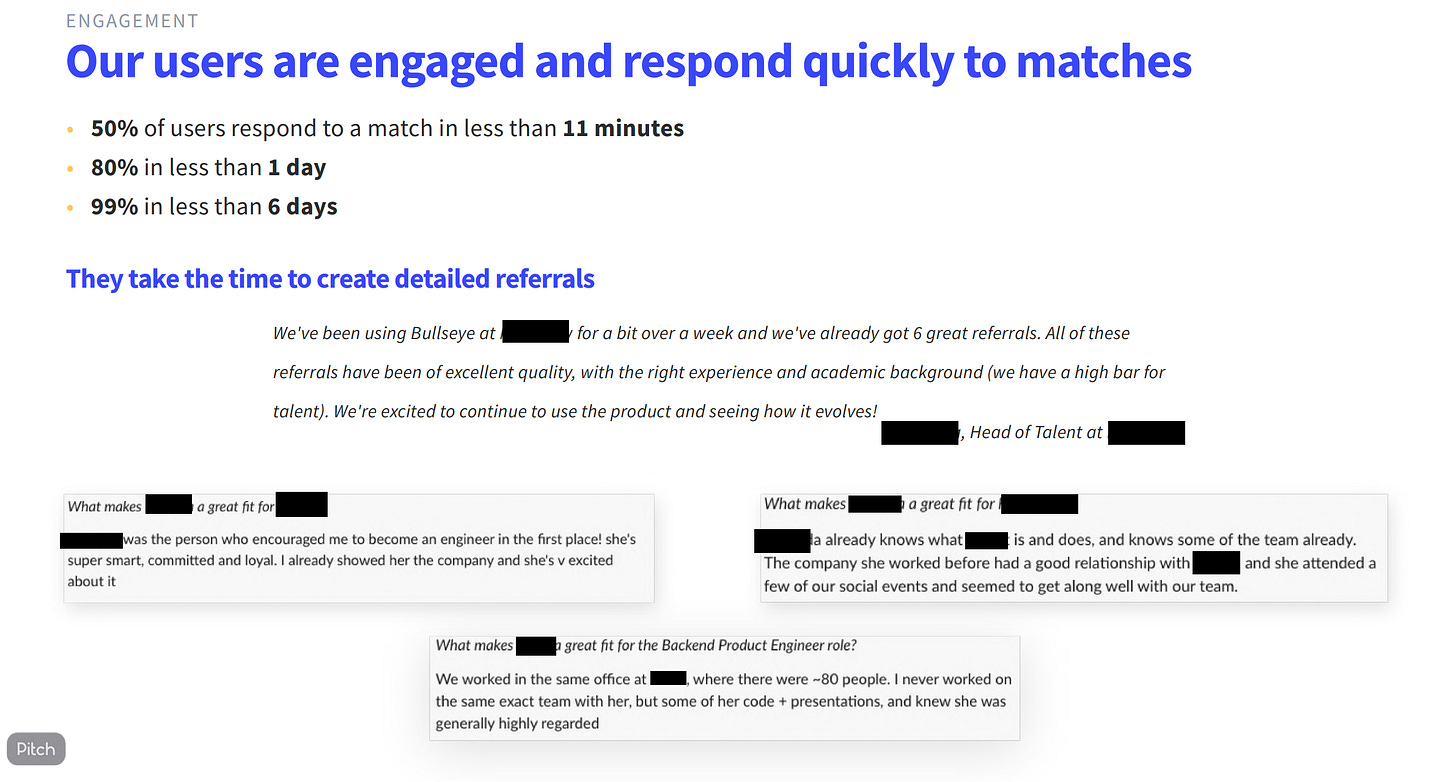

After breaking up my first team, I reconsidered and ended up working with my 2nd cofounder on employee referrals. We sprinted through 70+ user interviews in 2 weeks and learnt that Big Tech companies make beyond 30% of their engineering hires through referrals. Referrals are proven and work at scale. Yet this process is almost entirely manual and often run in a Google Sheet, taking hours of human time. At smaller companies, we learnt that referrals often fail to get beyond 5% of hires – for startups, it’s an untapped source of great people.

We’d validated a pain point and cofounded Bullseye.AI to solve it. We took this manual process - which often consists of locking a new hire in a room with a recruiter for an hour or two so they can manually search for their LinkedIn and ask for intros, the so called ‘recruiter shakedown’ - and automated it away. Whenever you hear about a Google Sheet workaround for a highly expensive business process, the SaaS fairy beats its wings:

Immediately we started to get traction. I had the network to get in with decisionmakers quickly and knew the space like the back of my hand. My cofounder was building at rapid speed. We signed up 8 companies, including $bn unicorns, as pilot customers and had a few 100 engaged users just a few days after launching our MVP, generating quality employee referrals every day.

We then pitched at EF’s Investment Committee and didn’t get funded. We got a split decision, a few yes and a few no, which turned into a pass. According to our venture partner, we were ranked as having top 20% traction amongst the cohort. We had built something that people wanted and were moving fast. But we got a no for 3 core reasons:

EF hated the market. The recruitment space is full of old problems – pretty much every EF company they have funded in the talent space has failed.

The macro timing was terrible. The longer we worked on Bullseye, the more the tech hiring market crumbled before our eyes (our IC was circa July 2022 as the layoffs started to roll in).

They were concerns with how defensible our idea was. If we start growing fast, what’s to stop a better funded American from cloning us?

We were told that they believed there was a $200m company in there - and that we were a great team to build it - but they weren’t convinced it was a $10bn fund returner so passed on investing. Good luck trying to explain to friends/family outside the tech world why building a $200m company is considered not good enough. I understood the math, but they all looked at me like I was batshit insane.

Far and away, the biggest mistake I made on EF was working on the wrong thing. Even though we had strong traction, it couldn’t overcome a bad market and terrible macro timing. I undervalued the importance of the market and, more importantly, ended up working in an area that I was no longer truly passionate about. If I’d stuck to my guns after breaking up with my first cofounder and never considered talent as a problem space, I would have seen a different branch of the future. For all future founders reading this, learn from my mistakes. This produced perhaps the most depressing to-do list ever:

Final tips

I want to finish this essay with a few concepts and tips that you should keep in mind going into EF.

The concept of high leverage

The concept of high leverage

The core idea here is that the output from your effort in life is not evenly distributed. We might call this the concept of high leverage. Sometimes your input creates 100-1000Xs more output than in normal times. You should live for these moments.

If you work really hard on EF and get a top outcome, that could see an acquisition from Facebook (like papersincode) that instantly nets you life changing wealth and the chance to impact billions of people (like shipping a state of the art LLM for science)

We can illustrate this concept with numbers. Let’s say your EF cohort has 70 members and 10 of them quit in the first few weeks. That means 60 people and a potential 30 teams. If those 30 teams stay true to the average and produce at least one $100m+ company, your chance of building something huge is at worst 1/30. Maybe if this is a particularly successful cohort - like EF’s fifth cohort with produced all of $100m+ valued Cleo, CloudNC and Credit Kudos - your chances could be as good as 1/10.

Compare that to pouring in 80 hour weeks as a Revolut engineer. The input (hours worked) is similar if not more, but the output (impact on the world, personal gain) is disproportionately less.

Salary negotiation is another classic example of high leverage. Before accepting a job offer, you are highly leveraged. If you put in just 10 minutes of your time to negotiate, you can net yourself an extra £XXk in salary. Alternatively, you can work extremely hard for half a year after accepting your offer, pouring in 100s of hours, and probably not get a raise. The point of negotiation is when you are highly leveraged, since a small input nets a massive output.

EF is one of the points in your life when you will be the most highly leveraged. Put in the work and you might change the world.

Primacy of the market

You should work on new problems in fast growing frontier markets (e.g. AI, biotech), unless you have a truly different take on an old problem. A great team with an awesome product will fail in a bad market. Much to everyones frustration, lazy teams can and do succeed in good markets. Don’t handicap yourself from the start. Read the Marc Andreessen classic ‘the only thing that matters’

Have trusted outside advisors

As founders, literally everyone wants to give you advice. You should select a few people that you really trust and can rely on, who should be former/current founders that are completely impartial. It’s important to have someone that you can call when the going gets tough. As we’ve covered already, EF can help, but there may be a mismatch of incentives since they have skin in the game.

You should make sure that your advisors are just one or two levels above you in the game, that is, Seed and Series A tier founders. The advice of people who are too many levels above you in the game or on a different kind of leaderboard (e.g. product VPs at big companies who have never worked pre PMF, non-VC founders) will be less relevant.

Think about meaningful founder exits

These are not the same as meaningful VC exits. It’s your life. Don’t play a hard, arduous and long game chewing glass and riddled with trap doors to make other people rich. Maybe you meet a cofounder and try to build a $50m company. You won’t get VC funded, but maybe, dependent on your success profile, that’s ok. You might even make more cash than the girl/guy that founds a $200m company if you play your hand right (dilution sucks). Think about what you want in life and stick to your guns. If you want to create massive impact and accrue unbelievable wealth and power, then EF will help you shoot for the billion dollar stars. If you don’t want to build at VC scale, EF isn’t the right place for you.

Manage your psychology

You should work extremely hard but remember, no one wants to work with a tired idiot. Watch ‘how to win’ by Daniel Gross, a former YC partner. This is great on viewing life as an infinite game.

Enjoy it

When else will you have the freedom to get paid money to test out startup ideas with some of the world’s smartest people? Don’t forgot to savour the journey too.

Apart from working on the wrong thing, I have few regrets about EF – I’d do it all again in a heartbeat. I found the best possible cofounder, but I didn’t work on the right idea.

If you’re applying to EF and want advice, my LinkedIn DMs are open. Want to build a massive company? You know what to do:

https://www.joinef.com

You can follow me on Twitter here and subscribe to my Substack below.

Thanks to Wim van der Schoot, Edward Alun-Jones, Boris Bubla, Amanda Pun and Ainhoa Arias Gimenez for reading drafts of this essay.

—

Throughout this essay I’ve often used cash as a proxy for impact/scale. To be clear, most of the people on EF are doing it for the impact, not the money. It’s harder to quantify and compare ‘impact’ across private companies with obfuscated data – cash is an easier yardstick we can use for rough illustrations of impact. There are better and significantly easier ways than EF to become rich: climb the FAANG ladder or work in finance. But, if you do want to become a billionaire, you should do EF or YC

Thanks Bill, lot of takeaways from this one. I really appreciate the thoughts on principles.

Great post and closely matches my experience with EF. Thanks for writing this piece.